Porcelain Insulator News

by Elton Gish, NIA #41

Reprinted from "INSULATORS - Crown Jewels of the Wire", April-May 1985, page 22

** NEW BOOK **

INSULATOR PATENTS, 1880-1960, by Jack H. Tod, 1985, softbound, 11" x 8-1/2", 130 pages, $20 plus

80 cents shipping.

This new book will be published this summer and is a must for every

collector, porcelain and glass alike. The book is a compilation of 695 insulator

patents represented on reference cards with a sketch of the insulator showing

the detail of the patent. There are six cards per page. If you have ever

searched through Official Patent Gazettes looking for a particular patent, you

can appreciate the thousands of thankless hours represented in this book from 80

years of patents; namely, 2,740,000+ letters patents and 177,000+ design patents

then making notes and sketches of each one that had anything to do with

insulators.

It is absolutely fascinating to see all these many designs of insulators.

Some are practical and others are of little use or too difficult to manufacture.

Can you believe 126 patents for self-tying insulators? The patents cover cleats,

knobs, both glass and porcelain pin types, non-pin types, wall tubes, tie-wire

clips, shields, pegs and pins, sleeves, suspension types and many other categories.

Literally every patent pertaining to the insulator hobby is illustrated in this

superb book with patent number, date and notes on each.

No one but Jack would have devoted so much time and energy to put together

this one-of-a-kind reference.

NOTE: There was a misprint in the December 1984 issue of CJ on page 24 in the

third paragraph from the bottom. It should read: "...and then a tapered

mandrel...". Obviously a threaded mandrel cannot be pushed into a threaded

hole without a little magic.

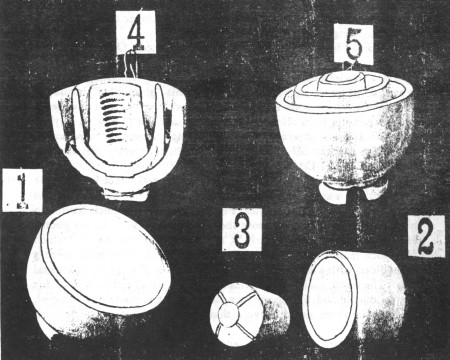

The following is a reprint from the April 5, 1902 issue of Electrical World

and Engineer, page 615 that I thought may be of interest. Note the grooves in

the center section (No. 3) to provide a channel for the glaze to flow and fill

the gap between the sections. There also are grooves in the second section. One

can be seen on the right-hand portion of No. 2 but probably will not show up

when the Xeroxed photo is reproduced here.

Boch's "Glaze-Filled" Insulator.

In the controversy between the advocates of porcelain and glass insulators

for high tension transmission lines, it is conceded for porcelain that it has

the advantage in respect to mechanical strength. The difficulty has been to make

high voltage insulators of porcelain uniformly free from flaws. When that has

been accomplished there can be little doubt that glass insulators can no longer

claim superiority in insulating quality over porcelain ones.

R. Thomas &

Sons' Company, of East Liverpool, Ohio, claim that their manager, Mr. J. W.

Boch, has accomplished the task of producing a flawless porcelain insulator of

superior insulating qualities as well as of great mechanical strength in his

"glaze-filled" insulator. This insulator has gone into practical use

during the past few years on high tension lines all over the country and has met

with marked success. It is of interest therefore to know how this insulator is

made, especially as Mr. Boch's patent has been recently sustained by the United

States Circuit Court.

Mr. Boch's invention is primarily based upon the fact

known ever since pottery was invented, that a thin piece of clay will mould and

vitrify better than a thick one. For this reason Mr. Boch builds up his

insulator out of two or more shells nested together. In the photo-engraving are

shown separately at 1, 2 and 3, the three shells of which Mr. Boch makes up his

triple petticoat insulator. The inner piece 3 is moulded with a suitable

threaded socket (see Fig. 4) for the usual pin. The outer shell 1 is provided

with the usual notched head for the conductor and like the intermediate part 2

is made bowl-shaped, so that the three are relatively thin shells, to he nested

into each other.

In the practice usually followed by R. Thomas & Sons'

Company, in making these insulators, these separately-molded parts are first

dried out separately, preferably in an oven or kiln in the usual manner of drying clay

articles by the process known as "biscuit firing". The

separate parts are then coated with glaze all over, as by dipping into liquid

glazing material, and they are then fitted into each other and stood upside

down, that is, petticoats uppermost, as in the position shown at 5. Extra

glazing material is supplied at the joints, that is, in the annular channels

between the petticoats.

The parts thus put together and supplied with extra

glaze at the joints are now put in the sagger with the petticoats of the

insulator uppermost and placed in a kiln, in which under great heat the clay

shrinks and becomes vitrified as usual and the glazing material melts and

becomes of a glass-like character, flowing down into and filling all the spaces

between the parts, such spaces either being there by lack of correct fit of the

parts or arising during the shrinkage of the clay by the vitrification. The separately

molded shells are thus welded together by seams of glass-like glaze, and this

welding has been found to be of so tenacious a character that the insulators can

be broken less easily along the lines of the "glaze-filled" seams than

elsewhere. The completed insulator is shown at 5, while at 4 is shown one cut in

two. This section clearly illustrates the three shells and the intermediate

"glaze-fillings," which, needless to say, add to the electrical

insulating qualities of the insulator as well as its mechanical strength.

|